Introduction & extracts

The Saxon monk and priest known as Wulfstan Cantor was Winchester’s first notable poet. He was also a musician and held the role of precentor (i.e. cantor) in the Old Minster (660-1093) in what was Europe’s largest church. As precentor he was responsible for organising and leading the sung worship, a role still found in Winchester and most other cathedrals today (and in part in most synagogues). A measure of his leadership, as the church’s musical director, is his probable role as the author of many hymns, mass settings and the chants found in the Winchester Troper.

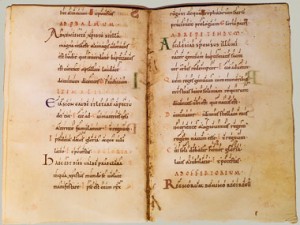

The Winchester Troper is a 200-page bound manuscript of 160 chants dating from c. 1000 and the copy held in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, was quite possibly Wulfstan’s own edition. The Troper is one of the largest collections of early church music and is significant both for its use of notation and its two-part musical settings, in which the late 10th century’s more creative precentors and composers were gracing Gregorian plainchant with ornamental harmonies.

However, it is as a poet that Wulfstan is of the greatest interest in Winchester’s literary history, together with his role in promoting the cult of St Swithun. He produced a biography of his mentor Bishop Æthelwold in 996 (Vita S. Æthelwoldi), numerous hymns and prayers, a treatise on musical theory, a poem of over 700 lines based on a sermon for All Saints, and his master-work, nearly 3400 lines of rhyming hexameter on the miracles of St Swithun (Narratio metrica de S. Swithuno), the longest, most stylish and accomplished poem of the Anglo-Latin era.

We know little of Wulfstan himself. He was an oblate, that is a pupil sent to the monastery aged seven or upwards, where he studied under Æthelwold; he took part in the rain-soaked 971 procession which translated Swithun’s bones from his tomb to a new shrine, and he was an eye-witness to the substantial reconstruction of the Old Minster, as recorded in his Narratio metrica.

Although it is as the biographer and propagandist for Swithun that he presents himself as a major poet, Wulfstan’s first great work was his life of Winchester’s Bishop Æthelwold, who was born in Winchester in 909 and was the see’s bishop from 963-984. Æthelwold was a zealous figure in the monastic reforms of the 9th century (expelling all the secular clergy from the monasteries and churches in Winchester by 971 and replacing them with Benedictine monks), an enthusiastic patron of the arts (Winchester’s manuscript illumination flourished during his episcopy), a keen builder and something of a plumber (he created the Lockburn drainage system for the monks which can still be found threading its way through the town), and he was instrumental in exhuming the bones of Swithun from his tomb outside the west door of the Old Minster to a shrine within the church in July 971 and so beginning the cult of St Swithun as a miracle worker.

The entire point of the sanctification of Swithun and the creation of the New Minster at Winchester, to house his shrine, was to attract pilgrims. In the words of the great medievalist and Swithun scholar Michael Lapidge, the aim was to create a focal point for the veneration of the saint, attracting large numbers of pilgrims (and hence revenue).1LAPIDGE, Michael, 2003. The Cult of St Swithun. Oxford: OUP Clarendon Press (Winchester Studies 4.ii). Professor Lapidge’s magisterial study of St Swithun is essential for any study of Anglo-Latin and medieval literature and I am grateful for his transcriptions of Wulfstan’s manuscripts.

Swithun seems to have been a pretty saintly bishop (852-862) even before his canonization in 971. The first account of him was by another monk at Winchester, Lantfred, who originally came from the great Benedictine abbey at Fleury near Orléans (an association still recalled daily at evensong in Winchester Cathedral). Lantfred’s hagiography, Translatio et miracula S. Swithuni, provided superb material for Wulfstan’s own poem some twenty years later, the Narratio metrica. Regrettably, however, and despite its technical brilliance and the insights into 10th century spiritual life, Wulfstan’s poem makes for laborious reading. Its litany of forty four miracles would tire the patience of a saint: ‘concerning the blind man whom his angry guide abandoned far from lodgings’, ‘concerning the three blind women and the dumb youth’, ‘concerning the slave-girl of Teothic the bell-founder’, ‘concerning the paralytic from Rochester’, but the best known of Swithun’s miracles, concerning the woman and the broken eggs, yields a significant literary treasure.

The story goes that some men, working on the all-important stone bridge over the Itchen at East Gate, jostled a women and caused her to drop a basket of eggs. Happily for her, Swithun was also there, supervising the construction of the bridge, and he made the seven eggs whole again. East Gate was the main entry into the city from London and Swithun’s new bridge was an essential contribution to the city, the Itchen then being a much broader river than today’s canalised torrent through the Weirs. As befitted such a significant piece of civic engineering, the Roman influence of lettering lingered on in Winchester and a Latin titulus was inscribed either on to the East Gate itself or the finished bridge, celebrating its construction by Swithun in 859. This inscription formed the basis of a ten-line poem, naturally also in Latin, which exists in the same manuscript as Wulfstan’s Narratio metrica de S. Swithuno. The poem, composed between the death of Swithun in 863 and his reburial in 971, is unattributed and it’s certainly not by Wulfstan. However, it is the earliest extant Anglo-Latin poem written in and about Winchester. The original is given here (in a transcription by Michael Lapidge) and then in a modern translation by Lesley Saunders, published here for the first time. 2Lesley Saunders, poet, educationalist and Latinist, is the author of several collections of poetry, including Christina the Astonishing (co-authored with Jane Draycott) published by Two Rivers Press 1998, Cloud Camera (Two Rivers Press 2012) and Nominy-Dominey (Two Rivers Press 2018).

Titulus on a bridge built by St Swithun

Hanc portam presens cernis quicumque viator

devotas effunde preces ad celsitonantem

pro Christi famulo SWIDUN, antistite quondam.

Per cuius summam cum sollicitudine curam

est huius pontis constructa operatio pulchra

ad Christi laudem, Wentane urbisque decorum,

sol octingentos cum rite revolveret annos,

quinquaginta novem replicaret et insuper annos

incarnata fuit postquam miseratio Christi;

tunc erat et vertens indictio septima cursum.

St Swithun’s Bridge

Traveller, whoever you may be, as your gaze rests

on this city-gate, take a moment to say a prayer, speak it

with a whole and humble heart to Him who makes

the heavens ring. Do this for Christ’s servant Swithun,

once bishop here: he spared no effort, no expense,

to have this elegant structure built, this splendid bridge,

to adore our Christ and adorn our town of Winchester.

The sun had circled eight hundred times and fifty nine

on its ordained yearly journey since Christ’s pity

had taken fleshly form: it was in the seventh tax cycle.

Translation copyright © Lesley Saunders 2013.

Wulfstan’s poem on St Swithun, longer even than Beowulf, written during 992-4 and finalised in 996, includes a long verse preface to Bishop Ælfheah (Æthelwold’s successor) in which he describes in lavish detail the reconstruction of the Old Minster, work started by the one bishop and completed by the other. This dedication is altogether more enjoyable reading than the accounts of miracles and there are two memorable passages. The first, quite well known to organ scholars, ‘Concerning the organ’, describes the improbably mighty organ housed in the church, and the second, in even more hyperbolic style, celebrates the minster’s tower.

Concerning the organ

Such organs as you have built are seen nowhere, fabricated on a double ground. Twice six bellows above are ranged in a row, and fourteen lie below. These, by alternate blasts, supply an immense quantity of wind, and are worked by seventy strong men, labouring with their arms, covered with perspiration, each inciting his companions to drive the wind up with all his strength, that the full-bosomed box may speak with its four hundred pipes which the hand of the organist governs. … Like thunder the iron tones batter the ear, so that it may receive no sound but that alone. To such an amount does it reverberate, echoing in every direction, that everyone stops with his hands to his gaping ears, being in no wise able to draw near and bear the sound, which so many combinations produce. The music is heard throughout the town, and the flying fame thereof is gone out over the whole country.3MATTHEWS, Betty, 1975. The Organs and Organists of Winchester Cathedral. 2nd ed. Winchester: Friends of Winchester Cathedral. This unattributed translation also appears in BLAKISTON, J M G, 1970. Winchester Cathedral: an anthology. Winchester: Friends of Winchester Cathedral.

The Tower is Raised

And besides which, you [ i.e. Ælfheah] had a sacred structure added, so tall that daylight there is uninterrupted by night. Your tower flashes from the vault of heaven as the rising sun catches it, splashing the first drops of dawn light on its stone.

Belfry-windows look out from each of its five storeys in all four directions over the land. The tower’s upper ramparts arch and glisten, its roofs are recessed with rows of arcades: the designer’s ingenious expertise – which is wont to add beautiful touches to beautiful spaces – taught the builders how to construct such curves.

High above rears the structure of a gilt-knobbed lightning-rod – its golden splendour enriches the whole edifice. Whenever the moon irradiates the church with its crowned rising, an answering brightness soars from the holy building to the stars. If a traveller were to set eyes on this during a night’s passing, he might credit the earth with possessing stars of its own.

An additional embellishment takes the form of a weathercock standing on the topmost point, covered in gold, glorious to behold. He looks down over the whole countryside, almost airborne above the fields, able to make out the splendid constellations of the stellar north. The bird holds the sceptre of power in its proud talons, and stands watch over all the townspeople of Winchester. He rides the winds, lords it over all other roosters, rules the kingdom of the west. Eager to receive the rain and winds from every compass point, he revolves on his axis and turns his face towards them; bravely he suffers the roaring force of gales, standing there unperturbed, enduring even bitter snowstorms. Only he can see the daystar sinking into the ocean, only he spies the first spokes of sunrise.

From a distance someone coming here may fasten his gaze on the weathervane as soon as he sees it and fix his direction by it for the rest of the way. And so the weary traveller is hurried along by what he marvels to see – the vision closes the distance for him even though his feet are still far away.

What else is there for me to say? You work at these things with all the talent and expertise at your disposal, to make the minster utterly beautiful from every point of view!

Translation copyright © Lesley Saunders 2013.

What to see

Nothing remains of the Old Minster but its ground plan is artfully laid out just to the north of the cathedral, and the cathedral has a memorial to St Swithun, the original shrine having been destroyed in 1538.

There are several churches dedicated to Swithun on the Pilgrims’ Way, a 112-mile journey from Winchester to Canterbury, via Farnham, the most important of medieval pilgrimage routes. St Mary’s Church in Kings Worthy, for example, has a late 15th century stained glass roundel depicting St Swithun and St Birinus; St Swithun upon Kingsgate has a 19th century glass depiction of Swithun and his bridge; while well away from this route in the Meon Valley, the Saxon church at Corhampton has some exceptional 12th century wall paintings with scenes from St Swithun’s life, one showing the famous incident on the bridge.

As for the first bridge over the Itchen, nothing remains of that but the anonymous 9/10th century poem.

Notes and references

| ↑1 | LAPIDGE, Michael, 2003. The Cult of St Swithun. Oxford: OUP Clarendon Press (Winchester Studies 4.ii). Professor Lapidge’s magisterial study of St Swithun is essential for any study of Anglo-Latin and medieval literature and I am grateful for his transcriptions of Wulfstan’s manuscripts. |

| ↑2 | Lesley Saunders, poet, educationalist and Latinist, is the author of several collections of poetry, including Christina the Astonishing (co-authored with Jane Draycott) published by Two Rivers Press 1998, Cloud Camera (Two Rivers Press 2012) and Nominy-Dominey (Two Rivers Press 2018). |

| ↑3 | MATTHEWS, Betty, 1975. The Organs and Organists of Winchester Cathedral. 2nd ed. Winchester: Friends of Winchester Cathedral. This unattributed translation also appears in BLAKISTON, J M G, 1970. Winchester Cathedral: an anthology. Winchester: Friends of Winchester Cathedral. |

Fascinating to read, best wishes from the wirral….E