Introduction

In January 1819 the poet John Keats spent two days in Chichester, where he started writing The Eve of St Agnes. The house he stayed in still stands and is marked with a commemorative plaque. In Bedhampton, just west of Havant, he stayed for a couple of weeks finishing the poem and the house he stayed in still stands. In Winchester, where he lodged for nearly two months between August and October 1819, wrote his last great ode and fifteen of his glorious letters, there is not a trace of any house he might have stayed in.

However, his ode To Autumn, inspired by and written in Winchester, is one of the most celebrated and enduringly popular poems in English literature. Keats’s 241 letters – witty, exuberant, bashful, anguished, loving and constituting an autobiography of sorts – were written with brio and ardently tailored to their recipients. His letters from Winchester show a great relish for the city which he describes with amused if diminishing affection, while the surrounding country offered a healthy respite from the many anxieties of his life.

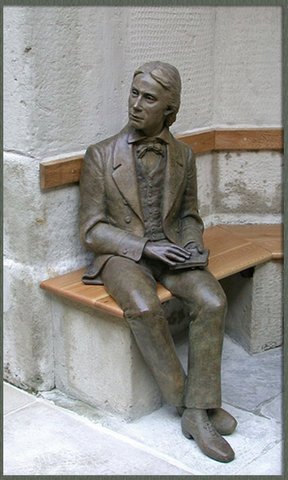

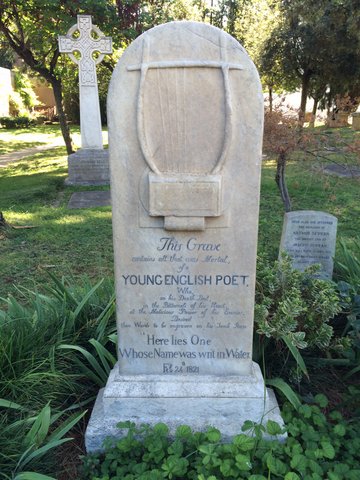

John Keats straddles English literature as one of its most cherished and of course romantic heroes. He is the poet above all others whom most poets revere and love reading. His artistic and emotional honesty, painfully evident in his letters, and his sensitivity, understandably, to literary criticism and gossip, have made him a soul-mate to many. Shelley’s elegy Adonais was published in the year of Keats’s death in 1821, and more recent homage includes A Kumquat for John Keats (Tony Harrison, 1981), Voyages (Amy Clampitt, 1985), Keats Country (F. T. Prince, 1995) and Jo Shapcott’s ‘Dr Keats’ sequence (Southword 2016).

Keats arrived in Winchester on 12 August 1819, fresh from Shanklin on the Isle of Wight and in company with his great friend Charles Brown. He was stimulated by new places and in addition he assumed he’d find a library in Winchester. There were two significant libraries in the city: the Morley Library in the cathedral and the Fellows’ Library in Winchester College, but both were pretty well out of bounds to indigent young poets. There were though several bookshops in the city, such as Greenville’s at 42 High Street and P & G Wells (then trading as James Robbins) in College Street.

The question of precisely where he lodged from August to October is unanswerable. His letters offer tantalising clues but at no point does he provide the address, although his first night in Winchester may have been spent at an inn near the High Street (see his letter of 20 September below). Some literary detectives have identified the handsome Minster House, opposite the west front of the cathedral, but this fails on two counts: there is no beautiful ‘blank side of a house’ on which he could gaze free of distraction from his first-floor room; and it is unlikely that he would leave by the back gate in order to walk to the front of the house on his way to the cathedral and the water meadows. On the evidence of the route he habitually took on his way to the water meadows, described in his letter of 21 September, it seems that he found reasonably smart lodgings in Colebrook Street, adjacent to the north-east corner of the cathedral graveyard.

Extracts

From the Winchester letters of John Keats1Forman, Maurice Buxton, ed., 1947. The Letters of John Keats. London: OUP.

TO Benjamin Bailey, friend, 14 August 1819

We removed to Winchester for the convenience of a Library and find it an exceeding pleasant Town, enriched with a beautiful Cathedrall and surrounded by a fresh-looking country. We are in tolerably good and cheap lodgings [and] As far as I know we shall remain at Winchester for a goodish while.

TO Fanny Brawne, girlfriend, 16 August 1819

This Winchester is a fine place: a beautiful Cathedral and many other ancient buildings in the Environs. The little coffin of a room at Shanklin is changed for a large room, where I can promenade at my pleasure – looks out onto a beautiful – blank side of a house. It is strange I should like it better than the view of the sea from our window at Shanklin. I began to hate the very posts there – the voice of the old Lady over the way was getting a great Plague.

TO Fanny Keats, sister, 29 August 1819

You must forgive me for suffering so long a space to elapse between the dates of my letters. It is more than a fortnight since I left Shanklin, chiefly for the purpose of being near a tolerable Library, which after all is not to be found in this place. However we like it very much: it is the pleasantest Town I ever was in, and has the most recommendations of any. There is a fine Cathedrall which to me is always a source of amusement, part of it built 1400 years ago; and the more modern by a magnificent Man, you may have read of in our History, called William of Wickham. The whole town is beautifully wooded – From the Hill at the eastern extremity you see a prospect of Streets, and old Buildings mixed up with Trees. Then there are the most beautiful streams about I ever saw – full of Trout. There is the Foundation of St Croix about half a mile in the fields – a charity greatly abused. 2By its Master, son of the egregious Brownlow North, Bishop of Winchester. We have a Collegiate School, a roman catholic School; a chapel ditto and a Nunnery! And what improves it all is, the fashionable inhabitants are all gone to Southampton.3Then something of a spa town. We are quiet – except a fiddle that now and then goes through my Ears. Our landlady’s Son not being quite a Proficient. I have still been hard at work, having completed a Tragedy I think I spoke of to you [Otho the Great].

TO John Taylor, publisher and friend, 5 September 1819

Since I have been at Winchester I have been improving in health – it is not so confined – and there is on one side of the city a dry chalky down where the air is worth sixpence a pint.

TO John Reynolds, friend, 21 September 1819

I am surprized myself at the pleasure I live alone in. I can give you no news of the place here, or any other idea of it but … How beautiful the season is now – How fine the air. A temperate sharpness about it. Really, without joking, chaste weather – Dian skies – I never lik’d stubble fields so much as now – Aye better than the chilly green of the Spring. Somehow a stubble-plain looks warm – in the same way that some pictures look warm – This struck me so much in my Sunday’s walk that I composed upon it.4The ode To Autumn.

TO Richard Woodhouse, friend, advocate and editor, 21 September 1819

I should like a bit of fire tonight – one likes a bit of fire – How glorious the Blacksmiths’ shops look now. I stood to night before one till I was very near listing for one. … I shall proceed tomorrow. Wednesday – I am all in a Mess here – embowell’d in Winchester. I wrote two Letters to Brown one from said Place, and one from London, and neither of them has reach’d him. … Some curious body has detained my Letters. I am sure of it. They know not what to make of me – not an acquaintance in the Place – what can I be about? So they open my letters. Being in a Lodging house, and not so self-will’d, but I am a little cowardly I dare not spout my rage against the Ceiling. Besides I should be run through the Body by the major in the next room. I don’t think his wife would attempt such a thing. Now I am going to be serious.

TO Charles Dilke, friend, 22 September 1819

Had I not better begin to look about me now? If better events supersede this necessity5of literary and political journalism what harm will be done? I have no trust whatever on Poetry. I don’t wonder at it – the marvel is to me how people read so much of it. I think you will see the reasonableness of my plan. To forward it I purpose living in cheap Lodgings in Town, that I may be in reach of books and information, of which there is here a plentiful lack. … Talking of Pleasure, this moment I was writing with one hand, and with the other holding to my Mouth a Nectarine – good god how fine. It went down soft pulpy, slushy, oozy – all its delicious embonpoint melted down my throat like a large beautiful Strawberry. I shall certainly breed.

TO George & Georgiana Keats, brother and sister-in-law; this long journal-letter was written over ten days from 17-27 September 1819

[17 September] I was closely employed in reading and composition, in this place, whither I had come from Shanklin, for the convenience of a library. … My name with the literary fashionables is vulgar – I am a weaver boy to them – a Tragedy would lift me out of this mess. And mess it is as far as regards our Pockets. But be not cast down any more than I am; I feel I can bear real ills better than imaginary ones.

[18 September] This Winchester is a place tolerably well suited to me; there is a fine Cathedral, a College, a Roman-Catholic Chapel, a Methodist do [ditto], and independent do, – and there is not one loom or any thing like manufacturing beyond bread & butter in the whole City. There are a number of rich Catholics in the place. It is a respectable, ancient aristocratical place – and moreover it contains a nunnery. Our set are by no means so hail fellow, well met, on literary subjects as we were wont to be.

[20 September] This day is a grand day for Winchester – they elect the Mayor. It was indeed high time the place should have some sort of excitement. There was nothing going on – all asleep – Not an old Maids Sedan returning from a card party – and if any old women have got themselves tipsy at christenings they have not exposed themselves in the Street. The first night tho’ of our arrival here there was a slight uproar took place at about ten of the clock. We heard distinctly a noise patting down the high street as of a walking cane of the good old dowager breed; and a little minute after we heard a less voice observe ‘What a noise the ferril made – it must be loose.’ Brown wanted to call the Constables, but I observed ‘t was only a little breeze and would soon pass over. The side-streets here are excessively maiden lady like. The door steps always fresh from the flannel. The Knockers have a very staid, serious, nay almost awful quietness about them. I never saw so quiet a collection of Lions and rams heads – The doors are most part black with a little brass handle just above the Key hole – so that you may easily shut yourself out of your own house – he! he! There is none of your Lady Bellaston rapping and ringing here – no thundering-Jupiter footmen, no opera-trebble-tattoos – but a modest lifting up of the knocker by a set of little wee old fingers that peep through the grey mittens, and a dying fall thereof. The great beauty of Poetry is, that it makes every thing every place interesting – The palatine venice and the abbotine Winchester are equally interesting.

[21 September] You see I keep adding a daily sheet till I send the packet off … I told Anne, the Servant here, the other day, to say I was not at home if any one should call. I am not certain how I should endure loneliness and bad weather together. Now the time is beautiful. I take a walk every day for an hour before dinner and this is generally my walk. I go out at the back gate across one street, into the Cathedral yard, which is always interesting; then I pass under the trees along a paved path, pass the beautiful front of the Cathedral, turn to the left under a stone door way, – then I am on the other side of the building – which leaving behind me I pass on through two college-like squares seemingly built for the dwelling place of Deans and Prebendaries – garnished with grass and shaded with trees. Then I pass through one of the old city gates and then you are in one College Street through which I pass and at the end thereof crossing some meadows and at last a country alley of gardens I arrive, that is, my worship arrives at the foundation of Saint Cross, which is a very interesting old place, both for its gothic tower and alms-square, and for the appropriation of its rich rents to a relation of the Bishop of Winchester. Then I pass across St Cross meadows till you come to the most beautifully clear river – now this is only one mile of my walk I will spare you the other two till after supper when they would do you more good.

TO Benjamin Haydon, artist and friend, 3 October 1819

Though at this present “I have great dispositions to write” I feel every day more and more content to read. Books are becoming more interesting and valuable to me. I may say I could not live without them. If in the course of a fortnight you can procure me a ticket to the british museum I will make a better use of it than I did in the first instance. … I came to this place in the hopes of meeting with a Library but was disappointed. The High Street is as quiet as a Lamb; the knockers are dieted to three raps per diem. The walks about are interesting – from the many Buildings and arch ways – The view of the high street through the Gate of the City, in the beautiful September evening light has amused me frequently. The bad singing of the Cathedral I do not care to smoke – being by myself I am not very coy in my taste. At St Cross there is an interesting Picture of Albert Dürers – who living in such warlike times perhaps was forced to paint in his Gauntlets – so we must all make allowances.

When Keats left Winchester for London in early October it marked the end of his ‘living year’ or his ‘fertile year’ as his biographers Gittings6Gittings, Robert, 1954. John Keats: the Living Year. London: Heinemann. and Bate7Bate, Walter Jackson, 1992. John Keats. London: Hogarth Press. describe it, the annus mirabilis of 21 September 1818 to 21 September 1819. During this remarkable twelvemonth, Keats produced Hyperion (abandoned) and The Fall of Hyperion (unfinished), The Eve of St Agnes, Eve of St Mark (unfinished), La Belle Dame sans Merci, odes on Indolence, Melancholy, a Grecian Urn and to a Nightingale, the historical dramas Otho the Great and King Stephen (unfinished), Lamia and of course the ode To Autumn. During this period he also nursed his dying brother Tom, wrestled with the family’s wretched finances, became engaged to Fanny Brawne and contracted tuberculosis. He was 24 years old.

The seven weeks in this exceptional year which culminated with his stay in Winchester were perhaps the most significant of all, if only for the tranquillity and beauty he found there and the burst of profound creativity. It was also from where, as he wrote to his friend and editor Richard Woodhouse on the night of 21-22 September, ‘I have determined to take up my abode in a cheap Lodging in Town and get employment in some of our elegant Periodical Works – I will no longer live upon hopes.’ After leaving Winchester he wrote little other poetry of note and 1820 was significant chiefly for the publication of Lamia (and other poems) in July and his departure for Italy in September; he died in Rome in February 1821.

Keats’s ode To Autumn is the most anthologised poem in the world,8Harmon, William, Quinn, Alice, Scott, Cindee, eds 1998. The Classic Hundred Poems. Columbia University Press. a recurrent entry in surveys of the nation’s favourite poems, and the flawless apotheosis of everything that he wrote. It also possibly has a secret life9Paulin, Tom, 2008. The Secret Life of Poems. London: Faber. as a republican commentary on the savagery of the Peterloo Massacre when government cavalry charged peaceful demonstrators in August 1819, the events fully reported in the Hampshire Chronicle. Keats certainly had considerable republican form, from his earliest work onwards, and was briefly in London during August, turning out with the huge crowds which welcomed the radical politician Henry Hunt on his return from St Peter’s Field in Manchester.

To Autumn

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cider-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too, –

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

What to see

Although Keats doesn’t give an address in any of his Winchester letters, much can be deduced from the plain guide to his stroll from the cathedral to the water meadows and St Cross. The 17-27 September journal-letter to his brother and sister-in-law in America indicates that his lodgings were at the western arm of Colebrook Street. This length of Colebrook Street had houses or tenements on both sides, for the most part lived in by small traders, carpenters, labourers; the area now occupied by the Guildhall and its car park was later home to a dye works and the Abbey Foundry. Between Colebrook Street and the cathedral grounds lay a parallel road, Paternoster Row. While Colebrook Street was smart enough for Keats’s house to also offer lodgings to an elderly major and his wife, scruffy Paternoster Row had long been the city’s principal public latrine and laundry area before the Lockburn stream was diverted and covered. Some of the larger properties on Colebrook Street had rear entrances on Paternoster Row, and at one point the tenements were pierced by a narrow alley known as Amen Corner (consider: Royal Oak Passage, Cross Keys or Hammond’s Passage). From this geography Keats’s directions make sense.

He goes ‘out at the back gate across one street, into the Cathedral yard’. This is only possible by leaving a house on the west side of Colebrook Street with a back gate onto Paternoster Row, after which he is in the cathedral grounds and taking the lime-tree walk, just opposite Amen Corner, and around the northern side until he reaches the front of the cathedral.

The next indicator of location is that his first floor – probably – room, faces the blank side of a house (which he celebrates because it offers no distractions to the writer at his desk). The ramshackle collection of 18th and 19th century houses formed a terrace with little prospect of a blank wall, apart from those at the gable end of the two terraces formed by the alley Amen Corner.10Thus positioning the location by one of the two tenements identified as Properties 564-562 in Keene, Derek, 1985. Winchester Studies 2: Survey of Medieval Winchester ii. Oxford: Clarendon Press. From this hypothesis it can be reckoned that the lodging house was on the site of either number 44a Colebrook Street or number 45.

Another location is suggested by the graceful Keats’ scholar Katharine Kenyon. This places the lodging house on the site of the present Paternoster House (originally built as a bakery in the 1880s), at the northern junction of Colebrook Street and Paternoster Row. This has its attractions, as the houses ranged along the south side of Colebrook Street were generally, and still are, of much better quality than the western arm of the street. However, Keats’s implication that he goes out of a back gate and crosses the street to the cathedral yard and its lime-tree walk, indicates a house which is closer to the alleyway.

Following the post-1945 re-planning of London by Sir Patrick Abercrombie, towns and cities all over the country embarked on substantial clearances of bomb sites, slums and derelict properties. Winchester joined in the demolition derby (though Abercrombie’s recommendations for Winchester were declined) and in 1955/56 about 450 city-centre houses were condemned and pulled down, including about 30 in Colebrook Street. Against this municipal cleansing, Keats’s lodging house stood little chance, especially considering the impetus to achieve car parking behind the Guildhall and, in 1961/63, the construction of the Wessex Hotel. The hotel car park stands squarely over the site of Amen Corner and the houses either side of it. The first edition of Pevsner’s Buildings of Hampshire and the Isle of Wight (1967) lauds the design and landscaping of the hotel – the second edition (2010) is far less complimentary. However, an architectural grace-note does record the location of Amen Corner with a pavement running east and west through the car park and the name Amen Court cut into the stone architrave.

The year before Keats arrived, a local historian, Charles Ball, had published An Historical Account of Winchester, With Descriptive Walks,11 Ball, Charles, 1818. An Historical Account of Winchester, With Descriptive Walks. James Robbins: Winchester. New edition 2009, Winchester University Press. an illustrated guide to six shortish walks around the city. It is hard to imagine that Keats had not bought a copy (despite Ball’s obsession with monumental inscriptions) if only to provide material for the tragedy King Stephen, whose reign was certainly tragic for Winchester. The final walk describes the mile-long route to St Cross and Ball gives directions leading from the Kingsgate and along Kingsgate Street before taking a path across a meadow to the medieval almshouses and church of the Hospital of St Cross. Interestingly, the route Keats describes is the somewhat muddier one generally taken by people today, going via College Street and College Walk, then alongside the River Itchen and through its water meadows.

When Keats arrived in Winchester in mid-August it was pretty well in the middle of harvest time and his pleasure in this contributed directly to the language of To Autumn. As poet and critic Tom Paulin describes it, ‘And so Keats composed his famous ode after a walk beside some stubble fields’12. Paulin gets this spot-on but there is a problem with the commonplace assertion that the famous walk was through the water meadows. There are no stubble fields in the water meadows. Water meadows are at best used by livestock and cannot be used for growing and harvesting wheat. Katherine Kenyon makes this point in her 1975 essay ‘Keats and the ode To Autumn walk’: ‘His biographers have assumed that it was on this mid-day walk to St Cross that he composed the ode To Autumn. But there were no cornfields among the water-meadows.'12KENYON, KATHERINE M R,1975. Keats and the ode To Autumn walk. Keats-Shelley Memorial Bulletin, No. XXVI, 15-17. Additionally, Keats only says in his letter to Reynolds of 21 September that ‘in my Sunday’s walk I composed upon it’, not in the least indicating that this was a walk to St Cross.

The fifth walk in Ball’s guide book takes the walker north out of the city to Hyde Abbey (or what was left of it), where he notes the recent use of the abbey gate as a barn. Kenyon argues that Keats had undoubtedly taken this walk as well, and further explored the Hyde Abbey millstream alongside Nuns Walk (or Monks Walk as it was known then). He would soon then have been in the arable country of Abbots Barton Farm, with a substantial second barn, a walled orchard, and on an excellent walk past bona fide stubble fields at Abbots Barton and towards Kings Worthy.

This is not to say that Keats didn’t mentally compose To Autumn while strolling southerly towards St Cross, as the ambiguous phrase to Reynolds describes it, but the immediate inspiration for his harvesting language can only have come from sauntering through the corn fields to the north of the city. For the last word, though, consider Keats’s comment in his journal-letter from Winchester to his brother and sister-in-law (18 September 1819):

‘You speak of Lord Byron and me – There is this great difference between us. He describes what he sees – I describe what I imagine. Mine is the hardest task.’

Notes and references

| ↑1 | Forman, Maurice Buxton, ed., 1947. The Letters of John Keats. London: OUP. |

| ↑2 | By its Master, son of the egregious Brownlow North, Bishop of Winchester. |

| ↑3 | Then something of a spa town. |

| ↑4 | The ode To Autumn. |

| ↑5 | of literary and political journalism |

| ↑6 | Gittings, Robert, 1954. John Keats: the Living Year. London: Heinemann. |

| ↑7 | Bate, Walter Jackson, 1992. John Keats. London: Hogarth Press. |

| ↑8 | Harmon, William, Quinn, Alice, Scott, Cindee, eds 1998. The Classic Hundred Poems. Columbia University Press. |

| ↑9 | Paulin, Tom, 2008. The Secret Life of Poems. London: Faber. |

| ↑10 | Thus positioning the location by one of the two tenements identified as Properties 564-562 in Keene, Derek, 1985. Winchester Studies 2: Survey of Medieval Winchester ii. Oxford: Clarendon Press. |

| ↑11 | Ball, Charles, 1818. An Historical Account of Winchester, With Descriptive Walks. James Robbins: Winchester. New edition 2009, Winchester University Press. |

| ↑12 | KENYON, KATHERINE M R,1975. Keats and the ode To Autumn walk. Keats-Shelley Memorial Bulletin, No. XXVI, 15-17. |