Introduction

The illuminated manuscript that is the Winchester Bible, cherished in Winchester Cathedral for over 800 years, is one of the glories of Western civilisation. However, it is not the only biblical treasure to which the city can lay claim. Winchester has played a sparkling role in the production of a later Bible, the King James authorised version, renowned throughout the world.

The story of translations of the Bible is one of exceptional scholarship, extraordinary personal courage and doctrinal persecution over many centuries. It is to the enduring credit of King James I of England (and VI of Scotland) that the English-language Bible he commissioned in 1604 wasn’t a brazenly new version but was to draw on the best of its predecessors, and particularly the Bishops’ Bible of 1568, which was itself rooted in William Tyndale’s heroic translation of the New Testament of 42 years earlier. Foxe’s Book of Martyrs recounts Tyndale’s furious rebuttal to a priest who claimed that canon law was more important than scripture, to the effect that ‘if God spared him life, ere many years he would cause the boy that driveth the plough to know more of scripture than he [the cleric] did.’ Of course, like the making of maps, all translation carries its own politics, and James’s desire was for a bible which unified previous interpretations, could be read to and by all and heralded his claims to embody spiritual and political unity.

The project began at the Hampton Court conference in January 1604, called by James to consider and resolve – to his satisfaction – the doctrines and governance of a divided Church of England. The suggestion for a new bible came from John Rainolds, the Master of Corpus Christi, Oxford and leader of the Puritan delegation to the conference. James had delighted in humiliating the Puritans in theological discourse but was quite shrewd enough to clasp the idea for all it was worth. The opposing delegates, the deans and bishops of the church, were aghast but nonetheless it was the Bishop of London, the odious Richard Bancroft, who became the project’s general manager. He was Archbishop of Canterbury by the end of the year and his zealous influence was invaluable in driving along the king’s hurry for completion. It was Bancroft who recruited the team of 54 translators required for the project and who issued, supposedly at the king’s direction, the 15 ‘Rules to be observed in translation’. This awesome set of instructions is testament to the power of a good brief and contributed greatly to the final result. One key direction was to exclude the controversial marginal notes which beset some previous translations, and which have been a feature of the more disputatious holy passages found in the Torah and the Qur’an.

The translators were drawn largely from the episcopacy and the universities (i.e. Oxford and Cambridge) and comprised the finest scholars, translators, editors and most ruthlessly ambitious clerics that England had to offer. Bancroft organised them into six groups, known as companies, each with its own leader and established them in pairs in Westminster, Cambridge and Oxford. Three companies were allocated portions of the Old Testament, two were given the New Testament and one was handed the Apocrypha, undoubtedly the poisoned chalice. What must have been the absolute pick of the bunch, the four Gospels, together with the Acts of the Apostles and Revelation, was given to the second Oxford company which met at Merton College, Oxford. Each of the translators was charged with working on the text at his own home or place of work, each working on the same texts. They then met collectively to consider what they had written, with the contributions being read out and the others only to comment if they wanted to contest a matter, otherwise it passed. This reading out loud of the work in progress was a key contributor to the rolling majestic sonority of the Bible’s language. As each company finished work on a particular book of the Bible it was to be sent to the other companies for independent scrutiny, probably the earliest practice of peer review in academic history. (Rule 9 of Bancroft’s briefing read ‘As any one Company hath dispatched any one Book in this Manner they shall send it to the rest, to be considered of seriously and judiciously, for His Majesty is very careful in this Point.’) This process took about four years from 1604 to 1608. The completed books were to be considered again and as a whole at a long series of editorial meetings held in the Stationers’ Hall in London during 1609-10. This review committee, working to the same oral process, comprised two men from each company, including the director of each, though it’s not certain that a dozen people were actually engaged in this task and it may have been just one member from each company. Finally, the finished text was put in the hands of two scholars to prepare for press, the first printed copies emerging from Robert Barker, Printer to the Kings most Excellent Majestie, during 1611.

And what of Winchester in all of this? During the years of translating the King James Bible there were three men living or working in the city who all had a substantial role in its production.

First, and least attractive, was Dr George Abbot, native of Guildford and still honoured there, despite his willingness to torture and call for the execution of heretics, his manslaughter of a Hampshire gamekeeper, his boundless clerical self-interest and utterly desiccated scholarship. He bought the post of Dean of Winchester for £600 in 1600 (while keeping his post as Master of University College, Oxford) and was Dean until 1609 when he became Bishop of Litchfield & Coventry, the following year Bishop of London and then Archbishop of Canterbury in 1611. It was joked at the time that he was translated twice before he saw the Bible translated once (translation being the term for appointment as a bishop). Nonetheless, he was an outstanding scholar and a significant member of the second Oxford company.

Barely less attractive was Thomas Bilson. Born in Winchester in 1547, educated at Winchester College and New College, Oxford, he was Headmaster of Winchester College in 1579, Warden of the College from 1581 to 1596 and finally Bishop of Winchester from 1597 until his death in 1616. He, too, raged against the Puritans at the Hampton Court conference and was a fierce theological polemicist. He wasn’t one of the translators but was one of the two men charged with seeing the final manuscript to press, which included writing all the preliminary matter and the chapter headings. His particular task, to which he was wholly suited given his shameless fawning as a courtier, was the dedication ‘To the Most High and Mightie Prince, JAMES by the grace of God, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, etc. The Translators of the Bible wish Grace, Mercy, and Peace, through JESUS CHRIST our Lord.’ Bilson follows this with ‘Great and manifold were the blessings, most dread Sovereign, which Almighty God, the Father of all mercies, bestowed upon us the people of England, when first he sent Your Majesty’s Royal Person to rule and reign over us’ and continues thus for a couple of excruciating pages. This dedication has invariably featured in most editions of the King James Bible for the past 400 years. By contrast, the 12,000 word Translators’ Preface, a superb essay on the art and craft of translation, is now scarcely seen in the King James Bible. It was written, possibly with input from Bilson and certainly his approval, by Dr Miles Smith, a member of the first Oxford company, a member of the review committee, and subsequently Bishop of Gloucester (1612) by way of reward for his work.

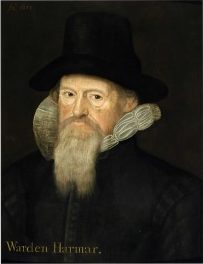

Thomas Bilson’s political skills did, however, have a significant impact on the third member of the Winchester triumvirate. When Bilson resigned as Warden of Winchester College and moved the two hundred yards to the Bishop’s Palace (via the see of Worcester) he nominated another old boy as his successor. John Harmar had followed in Bilson’s footsteps, first as a scholar at Winchester College, then fellow at New College, then Headmaster at Winchester College (1588-1595). However, Harmar’s 1596 bid to become Warden of Winchester College was rejected by Queen Elizabeth. She had recently appointed the dashing, worldly Sir Henry Savile, Warden of Merton College and once her Greek tutor, as Provost of Eton College, and she further intended to give the Winchester post to her chaplain Henry Cotton. (Savile, the only one of the translators not in holy orders, was also a member of the second Oxford company.) Harmar, strongly supported by Bilson and others, gamely stood up to Elizabeth during a protracted tussle, rather surprisingly won through and became Warden until his death in 1613.

John Harmar’s letter of petition to his monarch modestly describes his accomplishments rather well: ‘At Her Majesty’s last being in Hants she had the Scholars before her … at which time she vouchsafed to take notice of my being Her scholar, of my travels, of my being skilled in the tongues, Her professor, of publishing many things in print, and said she would have me in remembrance for my preferment.’1Quoted in Leach, Arthur F, 1899. A History of Winchester College. London: Duckworth. His reference to being ‘Her professor’ is because Elizabeth appointed him Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford in 1585, aged just thirty.

While it’s not possible to ascertain who wrote what among the second Oxford company of eleven translators, it’s certainly possible to identify some of the key players and John Harmar is undoubtedly one of the most significant.2I am indebted to Lachlan Mackinnon for igniting my interest in Harmar and to Dr Geoffrey Day, Fellows’ & Eccles Librarian, Winchester College, for generous provision of time and information about Harmar. He lacked the profile of Abbot, Savile or the group’s notional director, Thomas Ravis, but he was a polyglot, a European, an editor and clearly held in the highest regard by his peers. He knew Latin (obviously), Greek (of course) and quite probably Hebrew (invaluable) and possibly Syriac, or Aramaic (exceptional). During his twenties he studied on the continent, including lengthy stays in Paris and Geneva, then the centre of European biblical scholarship. This led to a friendship with the French theologian and scholar Theodore Beza, Calvin’s successor in Geneva and a noted literary stylist whose sermons Harmar published in Oxford. He also produced two editions of the sermons of St John Chrysostom, Patriarch of Constantinople and one of the most influential early Christian scholars, noted for his humanity and the egalitarian sweetness of his sermons, although not towards Jews. His name derives from the Greek soubriquet ‘golden-mouthed’ and Harmar’s 1586 edition of six of his sermons was the first book in Greek to be published in Oxford.

There are two interesting testaments to the worth of Harmar as biblical translator. When the revision committee met during 1609-10, to hammer out ‘doubts and difficulties’ from the six companies’ meetings, it was to comprise ‘the chief Persons of each Company’ according to Bancroft’s rules. It is moot whether the chief persons were one or two in number, i.e. a committee of six or twelve. What is certain is that Harmar was the second Oxford company’s man as he is the only translator named as such in notes taken during the Stationers’ Hall meetings. These detailed notes, taken by John Bois from the second Cambridge company, form a remarkable record of the care, passion and precision which the translators brought to their task. Bois’s notes, only discovered at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, in the 1950s3Allen, Ward, 1970. Translating for King James: Notes Made by a Translator of King James’s Bible. London: Allen Lane, the Penguin Press. are effortlessly tri-lingual: written in Latin, with constant references in Greek, and English as the target language. The 39 surviving pages of these notes largely record the sessions dealing with the Epistles, from Romans through to Revelation, the work of the second Westminster company. As in today’s minutes, comments are usually attributed to the particular committee members, with just five identified by their initials only plus John Harmar in full. It’s also notable that the works, and words, of St John Chrysostom are frequently consulted, although the version used was Sir Henry Savile’s magisterial edition begun in 1610.

The Oxford antiquary Anthony Wood, in his 1691-2 biographical dictionary of Oxford writers and ecclesiastics, describes Harmar as a ‘most noted Latinist, Grecian and divine.’ Wood, cantankerous and not wholly reliable, goes on to record the key fact that he ‘had a prime hand in the translation of the New Testament into English, at the command of King James.’ It is on John Harmar’s memorial plaque in New College Chapel, Oxford, however, that the most enduring testimony lives: Præsertim Novi Testamenti editione vernacular. ‘He … left many memorials of his learning and work, above all a vernacular edition of the New Testament: he expended faithful and fortunate effort at the royal command on the exegesis of the Greek original.’4Translated by Lesley Saunders.

There is a final consideration to Harmar’s value to the proceedings.5Norton, David, 2005. A Textual History of the King James Bible. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Rule 13 of Bancroft’s ‘Rules to be observed in Translation’ specifies the directors of each of the companies by their posts: ‘The Directors in each Company, to be the Deans of Westminster, and Chester for that Place; and the King’s Professors in the Hebrew or Greek in either University.’ This is somewhat at odds with ‘An Order agreed upon for the translation of the Bible’ in which the men of each company are listed, the first named being regarded as the director. In the case of the second Oxford company, the not-much-loved Thomas Ravis was therefore trumped by Rule 13. John Harmar had been Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford during 1585-1590, followed by Savile’s friend Sir Henry Cuffe from 1590-97 (executed for treason in 1601) and then John Perin, appointed in 1597 and therefore ostensibly director of the second Oxford company. However, Perin found the professorship too demanding of his time and resigned the appointment in January 1605, in which eventuality John Harmar, as a notable member of the company, might readily have become the de facto director.

The literary significance of the King James Bible is of course incalculable. Its role in carrying the English language to every part of the globe is without parallel, not to mention its prime purpose of conveying scripture to ploughboys. Although it took several decades for the Authorised Version to fully assume its revered place in the pulpit and by the hearth, its literary inspiration has been enormous for the best part of four hundred years. Few writers are uninfluenced by its language, phrasing, imagery, parables, its sheer nobility and narrative impact, or its dominant authority as a universal source of common understanding. The power of its language has occasionally led to speculation that Shakespeare must have had a hand in it. There is no evidence or circumstance to support this, although Rudyard Kipling’s rather waggish short story, Proofs of Holy Writ (1934), contrives an imaginary conversation between Shakespeare and Ben Jonson in which Dr Miles Smith of the first Oxford company secretly works with Shakespeare on a proof copy of some verses from Isaiah. Miles Smith would have needed little from the playwright, as this extract from his great preface shows.

Extracts from The Translators to the Reader

But how shall men meditate in that which they cannot understand? How shall they understand that which is kept close in an unknown tongue? as it is written, Except I know the power of the voice, I shall be to him that speaketh a barbarian, and he that speaketh shall be a barbarian to me. The Apostle excepteth no tongue; not Hebrew the ancientist, not Greek the most copious, not Latin the finest. Nature taught a natural man to confess, that all of us in those tongues which we do not understand are plainly deaf; we may turn the deaf ear unto them. … Therefore as one complaineth that always in the Senate of Rome there was one or other that called for an interpreter; so, lest the Church be driven to the like exigent, it is necessary to have translations in a readiness. Translation it is that openeth the window, to let in the light; that breaketh the shell, that we may eat the kernel; that putteth aside the curtain, that we may look into the most holy place; that removeth the cover of the well, that we may come by the water; even as Jacob rolled away the stone from the mouth of the well, by which means the flocks of Laban were watered. Indeed without translation into the vulgar tongue, the unlearned are but like children at Jacob’s well (which was deep) without a bucket or something to draw with: or as that person mentioned by Esay, to whom when a sealed book was delivered with this motion, Read this, I pray thee, he was fain to make this answer, I cannot, for it is sealed.

So the Syrian translation of the New Testament is in most learned men’s libraries, of Widminstadius his setting forth; and the Psalter in Arabick is with many, of Augustinus Nebiensis’ setting forth. So Postel affirmeth, that in his travel he saw the Gospels in the Ethiopian tongue: And Ambrose Thesius allegeth the Psalter of the Indians, which he testifieth to have been set forth by Potken in Syrian characters. So that to have the Scriptures in the mother tongue is not a quant conceit lately taken up, either by the Lord Cromwell in England, or by the Lord Radevile in Polony, or by the Lord Ungnadius in the Emperor’s dominion, but hath been thought upon, and put in practice of old, even from the first times of the conversion of any nation; no doubt, because it was esteemed most profitable to cause faith to grow in men’s hearts the sooner, and to make them to be able to say with the words of the Psalm, As we have heard, so we have seen.

Many men’s mouths have been opened a good while (and yet are not stopped) with speeches about the translation so long in hand, or rather perusals of translations made before: and ask what may be the reason, what the necessity, what the employment. Hath the Church been deceived, say they, all this while? Hath her sweet bread been mingled with leaven, her silver with dross, her wine with water, her milk with lime. … We hoped that we had been in the right way, that we had the oracles of God delivered unto us, and that though all the world had cause to be offended, and to complain, yet that we had none.

But it is high time to leave them, and to shew in brief what we proposed to ourselves, and what course we held, in this our perusal and survey of the Bible. Truly, good Christian Reader, we never thought from the beginning that we should need to make a new translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one; … but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones one principal good one, not justly to be excepted against; that hath been our endeavour, that our mark. To that purpose there were many chosen, that were greater in men’s eyes than in their own, and that sought the truth rather than their own praise. … The work hath not been huddled up in seventy two days, but hath cost the workmen, as light as it seemeth, the pains of twice seven times seventy two days, and more. Matters of such weight and consequence are to be speeded with maturity: for in a business of moment a man feareth not the blame of convenient slackness. Neither did we think much to consult the translators or commentators, Chaldee, Hebrew, Syrian, Greek, or Latin; no, nor the Spanish, French, Italian, or Dutch; neither did we disdain to revise that which we had done, and to bring back to the anvil that which we had hammered: but having and using as great helps as were needful, and fearing no reproach for slowness, nor coveting praise for expedition, we have at the length, through the good hand of the Lord upon us, brought the work to that pass that you see.

What to see

One of the additional pleasures of knowing that the Gospels were in part translated and edited in Winchester is that visitors can stand outside the very room in which much of the work was done. After he became Warden of Winchester College in 1596, John Harmar set about creating a study for himself in the Warden’s lodgings. Though the lodgings were greatly enlarged by his predecessor Bilson (the college’s first married Warden), Harmar tackled the sine qua non of an adequate study by building a fair-sized first-floor room for himself over the college’s bakehouse. Guided tours of the college, available all year except between Christmas and the New Year, don’t include this study. However, anyone standing in College Street to the left of Outer Gate may look up and see the study’s two windows, framing the embedded college shield with the completion date of 1697 and John Harmar’s initials. These are given as IH rather than JH, being the Latin (and indeed biblical Greek) form of his name, Ioannes.

While Harmar was at work on the Gospels in College Street, George Abbot, Dean of Winchester, may have been at work on the same material in the Deanery in the inner close of the Cathedral (though more likely to have been found in Oxford) and in the final stages of the publication, Thomas Bilson, Bishop of Winchester, may have been found in Wolvesey Palace writing the dedication and helping prepare the book for press.

There is one final King James Bible connection with Winchester, and this possibly the best of all, though not contemporary with the rest. Lancelot Andrewes was the director of the first Westminster company of translators (responsible for the first twelve books of the Old Testament) and the ipso facto editorial director of the entire translation. He was revered for his sermons, savoured for his calm wisdom, his challenging intellect and as a literary stylist. His sermons and essays have been championed for their style, not least by T S Eliot but, while undoubtedly stylish, they make cumbersome reading nowadays. He was Dean of Westminster in 1601, Bishop of Chichester 1605-1609, then of Ely 1609-1619 and proved a highly effective Bishop of Winchester from 1618 until his death in1626. There is a fine sculpture of him by Simon Verity (1994-95) above his memorial plaque on the south side of the cathedral’s chancel.

Sources

Moore, Helen and Reid, Julian, eds 2011. The Making of the King James Bible. Oxford: Bodleian Library.

Nicolson, Adam, 2003. Power and Glory: Jacobean England and the making of the King James Bible. London: HarperCollins.

Norton, David, 2011. The King James Bible: A Short History from Tyndale to Today. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

A very fine account of his life and works on the Winchester College website.

Notes and references

| ↑1 | Quoted in Leach, Arthur F, 1899. A History of Winchester College. London: Duckworth. |

| ↑2 | I am indebted to Lachlan Mackinnon for igniting my interest in Harmar and to Dr Geoffrey Day, Fellows’ & Eccles Librarian, Winchester College, for generous provision of time and information about Harmar. |

| ↑3 | Allen, Ward, 1970. Translating for King James: Notes Made by a Translator of King James’s Bible. London: Allen Lane, the Penguin Press. |

| ↑4 | Translated by Lesley Saunders. |

| ↑5 | Norton, David, 2005. A Textual History of the King James Bible. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |