Introduction

It may be painful for Wintonians but Jane Austen was far more familiar with Basingstoke, and indeed Southampton, than she ever was with Winchester. She is of course buried in Winchester Cathedral and her sister Cassandra wrote that she was very fond of it, as indeed many people are. Her bookish father had an account at John Burdon’s bookshop in College Street (now P & G Wells); her music teacher, the Cathedral’s assistant organist George Chard, used regularly to ride to Steventon to provide piano lessons; several of her nephews attended Winchester College; her friends Mrs Elizabeth Heathcote and Miss Alethea Bigg lived in the Cathedral Close, and she is commonly believed to have danced at St John’s Assembly Rooms in the Broadway (though there is no evidence for this).

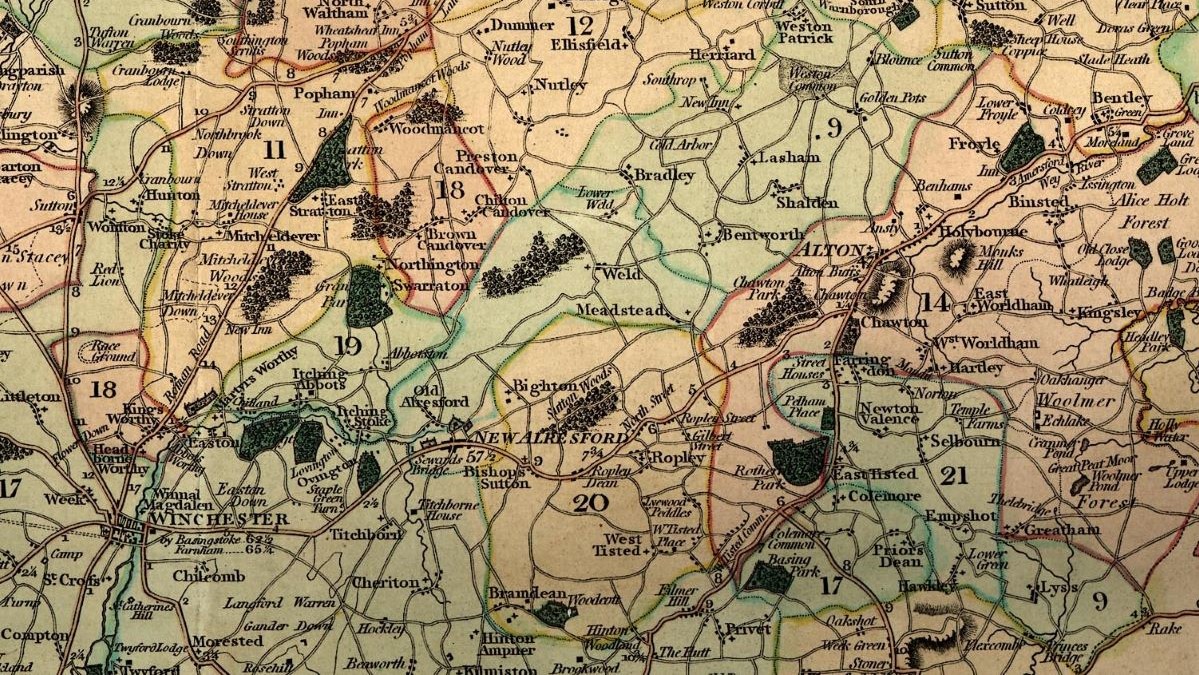

However, Jane Austen’s first twenty five years were spent very happily in her father’s rectory at Steventon, eight miles west of Basingstoke. Her dancing days were spent in the Assembly Rooms in Basingstoke or in the great country houses of the family’s many friends to the west and south west of the town. In 1801 the family moved to Bath, and more dancing, for five rather unhappy years and then to Southampton in 1806 for two and a half years, following the death of her father. Southampton proved more enjoyable to Jane (with plenty of dancing at the Dolphin Inn) and a fine river on which to take her nephews boating. Then in 1809 with her mother and elder sister she moved to Chawton, returning to the Hampshire countryside near Alton. This was the happiest move of all and came about due to her brother Edward’s good fortune. He had been adopted by his father’s very rich cousin and when he came into his substantial inheritance he was the owner of three fine estates, one in Kent where he preferred to live, one in Steventon and the other in Chawton. As successful sons often do, he eventually provided a house for his mother, and his two younger sisters, in the bailiff’s cottage in the middle of the village. Improvements were of course made to the property but it was still a cottage and in rather questionable contrast to the Elizabethan splendour of the great manor itself, Chawton House.

One shouldn’t look for too much autobiography in Jane Austen’s fiction but she is extremely prescient in her first published novel Sense and Sensibility, begun in 1795 when she was twenty and polished and polished thereafter until publication in 1811, about fifteen months after moving into Chawton Cottage. In the opening chapters of the novel it is possible to experience the emotions surrounding an elder brother’s adoption, the pain of being turfed out of a childhood home, of its graceless management by an elder brother and grasping sister-in-law, and then living in poignantly reduced circumstances:

“With the size and furniture of the house Mrs Dashwood was upon the whole well satisfied; for though her former style of life rendered many additions to the latter indispensable, yet to add and improve was a delight to her; and she had at this time ready money enough to supply all that was wanted of greater elegance to the apartments. ‘As for the house itself, to be sure,’ said she, ‘it is too small for our family, but we will make ourselves tolerably comfortable for the present. … These parlours are both too small for such parties of our friends as I hope to see often collected here; and I have some thoughts of throwing the passage into one of them … this, with a new drawing-room which may be easily added, and a bed-chamber and garret above, will make it a very snug little cottage. I could wish the stairs were handsome.”1AUSTEN, Jane, 1933. Sense and Sensibility. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press

The main consequence of returning to Hampshire’s countryside was that Jane Austen began writing again. While at Steventon she had begun her juvenilia at 12, all manner of satires, plays and poems to amuse herself and occasionally her family, and also started Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey. After settling in Chawton, she revised Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey, wrote Mansfield Park, then Emma and then Persuasion. Whatever the place of Winchester, Bath or Basingstoke in her life, it was clearly Hampshire, with its villages and country houses, which was the main stage for her creativity.

In Chawton, the Austen women exchanged Basingstoke for the somewhat more homely Alton as their nearest town. Winchester was sixteen miles away, by a goodish road, on a busy coaching route. Chawton Cottage stood right on the road itself, opposite the inn and close by the village pond and from its windows Jane Austen kept an amused eye on the human and wheeled traffic. Winchester barely figures in her letters from Chawton, with most references being about her nephews at the College, as well as this gleeful comment to one of them, James-Edward Austen, in July 1816: “We saw a countless number of Postchaises full of Boys pass by yesterday morning – full of future Heroes, Legislators, Fools, & Vilains.”2LE FAYE, Deirdre, ed., 2011. Jane Austen’s Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press

It was this very Hero, James-Edward Austen-Leigh, who was to publish the first biography of his aunt, in 1870, a memoir which maintained and promulgated the deceit of Jane Austen as a demure and maidenly spinster. After Jane’s death in 1817, her sister Cassandra destroyed some of the letters in her possession: those which might have reflected indiscreetly on their author and the family, leaving 160 extant, albeit many with waspish intent which escaped Cassandra’s censorship. Jane Austen was lively, fun, irreverent and engagingly acerbic, with the breezy insouciance of the well-born, if not the well-off. It’s little wonder that her nephews and nieces cherished her and even Cassandra can be forgiven her pyre for this tender letter to their niece Fanny Knight in Kent, two days after Jane’s death: “I have lost such a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as never can have been surpassed. She was the sun of my life, the gilder of every pleasure, the soother of every sorrow; I had not a thought concealed from her, and it is as if I had lost a part of myself.”3 LE FAYE, op.cit.

In literary terms, Jane was also poorly served by her elder brother Henry, amiable, charming and doing his best as an unofficial literary agent and then co-literary executor after her death. However, he was a man who had made such a hash of running his own bank that it folded, and his lacklustre efforts with London’s stony hearted publishers contributed to the six great novels being largely unknown except to bands of enthusiasts for the next fifty years. Jane’s father had rather sweetly offered to submit her first completed novel (titled ‘First Impressions’) to a publisher but it was promptly rejected without consideration. It was shrewd of the Rev George Austen to write to Thomas Cadell, who published the best-selling Fanny Burney and Charlotte Smith as well as David Hume and Samuel Johnson, but turning down the initial draft of Pride and Prejudice was a pretty startling blunder. Jane had slightly better luck when Henry secured an offer of publication for Northanger Abbey in 1803 from B. Crosby & Co, the publishing firm which dominated the book pages of the Hampshire Chronicle.4FACER, Ruth 2010. Fiction in the Hampshire Chronicle 1772 – 1829. Available at www.chawtonhouse.org/library/chronicle.html Crosby’s endless advertisements for fiction, travel, memoirs, gardening and children’s books might have encouraged Henry to think all was well, but after six years Jane’s novel still hadn’t been published; Crosby said she could buy back the copyright for the £10 they’d paid for it but she couldn’t afford to do this until 1816 when Henry retrieved the rights and it was published a few months after her death in 1818. Jane Austen’s first publisher, the military specialist Thomas Egerton of Whitehall, chose not to promote her first three books in the Hampshire Chronicle, the national Morning Chronicle sufficing; by 1818 four of the books were in the hands of the final and most favoured publisher, John Murray, who advertised the firm’s non-fiction in the Hampshire Chronicle but not his fiction list. The first collected edition of all six novels didn’t appear until 1833.

There is one piece of work by Jane Austen which is indisputably rooted in Winchester. It is a poem written just three days before her death in 1817, while she was lodging in College Street in the city, and is a droll complaint about the town’s citizens who profanely spend St Swithun’s Day at the races instead of their devotions. It was written, or more probably dictated to Cassandra, on St Swithun’s Day itself, perhaps as a response to wet weather, and it is her last composition. She enjoyed writing light and occasional verse, and had done so since childhood. Ironists may detect a deeply sardonic spirit underlying this poem, bearing in mind the saint’s reluctance to be buried inside the cathedral and what befell the original spire when his wishes were ignored.

Extract

Venta5Venta Belgarum was the Roman name for Winchester. The poem is predicated on the legend of rain for the next forty days if it rains on St Swithun’s Day (15 July). Swithun was a Bishop of Winchester and and there is a memorial shrine in the cathedral. The once-fashionable Winchester race-track was on Worthy Down to the north of the city.

Written at Winchester on Tuesday the 15th July 1817

When Winchester Races first took their beginning

It is said the good people forgot their old saint

Not applying at all for the leave of St. Swithin

And that William of Wykham’s approval was faint.

The races however were fix’d and determin’d

The company met & the weather was charming

The Lords & the Ladies were sattin’d & ermin’d

And nobody saw any future alarming.

But when the old Saint was inform’d of these doings

He made but one spring from his shrine to the roof

Of the Palace which now lies so sadly in ruins

And thus he address’d them all standing aloof.

Oh, subjects rebellious, Oh Venta depraved

When once we are buried you think we are dead

But behold me Immortal. – By vice you’re enslaved

You have sinn’d and must suffer. – Then further he said

These races & revels & dissolute measures

With which you’re debasing a neighbouring Plain

Let them stand – you shall meet with your curse in your pleasures

Set off for your course, I’ll pursue with my rain.

Ye cannot but know my command in July.

Henceforward I’ll triumph in shewing my powers,

Shift your race as you will it shall never be dry,

The curse upon Venta is July in Showers.

What to see

Jane Austen offers literary tourists two fine sites in Winchester and an exemplary one further afield. The Winchester sites are, regretfully, associated with her death. On 24 May 1817 the seriously ailing Jane was taken from Chawton by her brother’s carriage to 8 College Street where she lodged at Mrs David’s house. Mary David, or Mrs Bradfield as she had been, was a subscriber to the County Hospital, a substantial 112-bed hospital which dominated the east side of Parchment Street from 1759 until 1868. The County Hospital was of course for the poor and indigent and its chief surgeon was Mr Giles King Lyford, highly regarded by his peers. When the Alton apothecary William Curtis said he could do no more for Jane, this led to her move to Winchester where she could be treated by Lyford, who of course also had a thriving private practice. He lived in some style in St Thomas Street, in a substantial house on the south-east corner at the junction with St Clement Street (on the site now occupied by numbers 4, 5 and 6), and attended his patients in their own homes, or in this case the home of Matthew and Mary David. Mrs David’s support for the hospital in Parchment Street indicated a willingness to aid the sick and may have been a factor in Jane’s friend Elizabeth Heathcote recommending her house on College Street. Of Mary David we know little, except that she was 57 when Jane came to stay; her parish church of St Swithun upon Kingsgate records her death in October 1843 and she is buried by her second husband Matthew David in the Cathedral churchyard, within the locked enclosure on the north side.

However, Jane’s illness (generally now diagnosed as Addison’s disease, quite possibly Hodgkin’s disease, and the subject of much speculation) was beyond curing although Lyford’s treatment of her, and towards the family, was scrupulous and tactful. Jane Austen spent her final eight weeks in College Street, attended by Cassandra, her brothers, her friend Elizabeth Heathcote who lived a few hundred yards away in the Cathedral Close, and of course Lyford.

Elizabeth Heathcote, née Bigg, a friend of long-standing from her Steventon days who lived at Manydown Park, had in 1798 married the Rev William Heathcote from Hursley Park (to the west of Winchester). He lived in the Close as a cathedral prebendary, first at number 10 from 1798 to 1800 and then at number 2 from 1800 to March 1802, when he died aged 30, leaving his widow with a young son.6As Heathcote also had the living of Worting, between Manydown Park and Basingstoke, it’s quite possible that he lived there with his new wife in the handsome rectory, and let out the prebendal houses to which he was entitled. Or, he could just have attended to his parish once a week and chosen to live in the grander place nearer to his own family rather than his wife’s. She went back to her family home near Basingstoke and then, when her father died in 1813, she had to leave Manydown Park and returned to Winchester, where of course her son was at school. As Sir William Heathcote Bt, her son grew into a model landowner and was instrumental in bringing John Keble to Hursley. He was also something of a friend to the novelist Charlotte M Yonge of Otterbourne. It is worth noting what his biographer, a friend of the family called Frances Awdry, reports Heathcote as saying: “In April 1814 my mother fixed herself in the Close at Winchester, in the Prebendal House of the Rev. Philip Williams, an old friend of her father.”7AWDRY, F, 1906. A Country Gentleman of the Nineteenth Century: Being a short memoir of the Rt. Hon. Sir William Heathcote, Bart., of Hursley 1801 – 1881. Winchester: Warren & Son. Williams was a Greek scholar, taught at Winchester College and also had the living at Compton and so was able to let his house in the Close. This property was then number 12 and stands today, set back in the north-west corner of the Close, an elegant brick house dating from the 1660s, now privately rented from the Dean and Chapter.8CROOK, John, 1984. The Wainscot Book: The Houses of Winchester Cathedral Close and their Interior Decoration 1660-1800. Winchester: Hampshire County Council.

Thus, on occasional visits Jane Austen might well have stayed in three different Close houses while visiting Elizabeth Heathcote: number 10 (the cathedral’s current education centre), number 2 and number 12. Number 2, demolished in 1856, had been the home of Thomas Ken, one of England’s greatest hymn writers of the 17th century and eventually Bishop of Bath and Wells. By virtue of the Buggins’ turn which prevailed among the Close residents, Ken had also lived in number 11, but this house was demolished in about 1846, representing another literary loss9CROOK, op.cit.. Literary pilgrims today, though, can gaze at the house in the corner (now re-numbered 11) and know that Jane and Cassandra had stayed there for a week’s visit at the end of 1814. While gazing, they might also wonder why the estimable Mrs Heathcote chose later to fix Jane Austen in lodgings rather than in her own capacious house.10Elizabeth Heathcote lived in the Close until 1826 when she and her sister Alethea moved to Southend House in Hursley to be near her grand-children and then, as she aged, into Hursley Park with her son and his immediate family. She died in 1855 and is interred in the family mausoleum in Hursley churchyard. Southend House was demolished in 1967.

Three days after arriving in College Street, Jane Austen wrote a brave-hearted letter to her nephew James-Edward at Oxford, describing their lodgings as comfortable with a neat little drawing room and a bow window overlooking Dr Gabell’s garden.11LE FAYE, op. cit. The reference to Gabell is interesting: he was the College headmaster at the time and, in harness with the warden George Huntingford, presided over one of the most disorderly periods in the school’s long history. Several of Jane Austen’s nephews who attended the College were unfortunate to be there during this reign and she would have been well aware of Gabell’s ineptitude as head. However, his garden, on the north side of College Street where there is now open space, appears to have provided some solace.

The other significant site in the city is her gravestone, laid in the floor on the north aisle of the nave. Of the cathedral’s 300,000 annual visitors, many identify this tomb as a prime reason for their visit and this was recognised by the installation of a permanent exhibition to the writer in 2010. Surprise is often expressed by commentators that the epitaph – probably composed by her brother Henry – makes no reference to her as a novelist. It would be far more surprising if there had been such a reference in 1817 as only three of her novels had appeared by then, published anonymously and selling in small numbers, although to a most appreciative readership. She would have needed the fame of a Walter Scott or Mary Wollstonecraft before her achievements were incised in stone, and even the graves and tombs of such acclaimed writers as Aphra Behn, Maria Edgeworth or Fanny Burney (and Sylvia Plath in our own time) make no reference to their writing. All Henry can do is bravely refer to ‘the extraordinary endowments of her mind’ in the inscription and then, 55 years later, a memorial brass tablet of 1872 on the north wall of the nave begins by describing her as ‘known to many by her writings’. This was followed in 1900 by a memorial window above the tablet, more commemorative of Jane Austen’s piety than her art.

In the circumstances it is far more curious that Jane Austen is buried in the cathedral at all, but the clue to this is in Henry’s reference to her extraordinary mind. By the time of her death, she and her books were gathering an influential band of admirers and she was enjoying the literary attention. This band naturally included Mrs Elizabeth Heathcote, widow of a cathedral canon, resident in the Close and still with firm connections there; her father-in-law, Sir William Heathcote Bt of Hursley Park; brother Henry, ever enthusiastic and curate at Chawton; brother Edward Knight, lord of the manor at Chawton; and brother the Revd James, the eldest and like Mrs Heathcote, well acquainted with the Dean Thomas Rennell. Taken altogether, there was considerable social and literary weight behind the family’s undoubted desire for Jane to be laid to rest in the cathedral (rather than the crowded graveyard outside on the north side) and the Dean and Chapter appears to have played its part handsomely.

Had she lived, Jane Austen would have been aghast to see her childhood home, Steventon Rectory, pulled down in 1824 and astonished to know that Elizabeth Heathcote’s house near Steventon, Manydown Park, was demolished in 1965, together with Kempshott House and Hurstbourne Park in the same year, just three of the thirty or so Hampshire country houses destroyed during the twentieth century.12BECKETT, Matthew 2012. Lost Heritage. Available at www.lostheritage.org.uk However, of the other fine houses she knew, Ashe House survives, as does the Vyne, Worting House, Hackwood Park and Deane House. A far humbler survival, and rather more accessible, is the Wheatsheaf inn on the A30 at North Waltham between Basingstoke and Winchester; this Grade II listed building was in effect one of the Austens’ post offices, a two mile walk from Steventon and where letters and parcels could be collected. The other surviving coaching inn and post house is Deane Gate Inn, on the B3400 between Basingstoke and Overton.

Most gloriously – in literary rather than architectural terms – Chawton Cottage survives and flourishes as one of the finest writer’s houses in the country. The UK is fortunate to have dozens of writers’ houses and museums extant and open to the public, celebrating the life and work of their famous residents, but as the appeal of literary pilgrimage gathers pace, so does the voice of anti-heritage critics. This is April Bernard writing in the New York Review of Books: “Here’s what I hate about writers’ houses: the basic mistakes. The idea that art can be understood by examining the chewed pencils of the writer. That visiting such a house can substitute for reading the work. That real estate, including our own envious attachments to houses that are better, or cuter, or more inspiring than our own, is a worthy preoccupation. That writers can or should be sanctified. That private life, even of the dead, is ours to plunder.”13BERNARD, April, 2011. What I Hate About Writers’ Houses. The New York Review of Books, 22 December 2011, 78. Or, Anne Trubek’s ‘Skeptic’s Guide’: “Writers’ house museums expose the heartbreaking gap between writers and readers. Part of the pull of a writer’s house is the desire to get as close as possible to the precise, generative ‘Aha!’ But we can never get there. … Going to a writer’s house is a fool’s errand. … We can only walk through empty rooms full of pitchers and paintings and stoves.”14TRUBEK, Anne, 2011. A Skeptic’s Guide to Writers’ Houses. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Such complaints are less to do with post-structuralist criticism, where all that counts is the text and nothing but the text, than feelings of prurience over snooping and a natural reluctance to make shrines of buildings not designed for the purpose. However, as Nicola Watson reports in her admirable analysis The Literary Tourist15WATSON, Nicola J, 2006. The Literary Tourist: Readers and Places in Romantic Victorian Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan., the readers’ desire to experience the haunts, graves, houses of their heroes has a long history, with visits to Shakespeare’s birthplace getting underway in 1769. The business really took off during the nineteenth century with the deification of Sir Walter Scott and all his works, and has continued apace since then. Watson notes that one of the highlights of Katy Carr’s European tour, in What Katy Did Next (1886) was a visit to Winchester so “that Katy might have the privilege of seeing the grave of her beloved Miss Austen”. Katy’s encounter with an oddly cockney verger by the grave, complete with aspirated vowels, deals with a favourite cathedral legend, that the staff hadn’t a clue who Jane Austen was, although if they’d read their own 1854 handbook all would have been clear.

As for Chawton Cottage, the visitor is richly rewarded in several ways. Visitors can savour, for example, the full Austenesque anguish of class, money and social standing by strolling the few hundred yards from the comfortable, cosy cottage she lived in towards the grandeur of her brother Edward’s Chawton House, all the while pondering life’s unfairness and inequality, most especially for women. Without reference to the geography and environment of this, or any other literary ‘place’, it can be difficult to experience and appreciate such contrasts.

(Happily, Chawton House is now a study centre and library focussing on women’s writing in English from 1600 to 1830. The estate came close to dereliction during the 20th century but was restored by 2003 and the stairs are still exceeding handsome.) In Chawton Cottage itself stands perhaps the most poignantly intimate of all the curated artefacts, the small round occasional table Jane Austen used to write upon. Another legend, dating from her nephew’s 1870 memoir, refers to her desire to maintain the creaking of a door to forewarn her of intruders while she was writing and so conceal the page she was working on. It’s impossible to believe that this was a serious concern when she was writing, whether letter, manuscript or shopping list, in a small busy house with creaking floorboards, and her mother, sister and their friend Martha Lloyd all knowing perfectly well what she was about.

Why number 8?

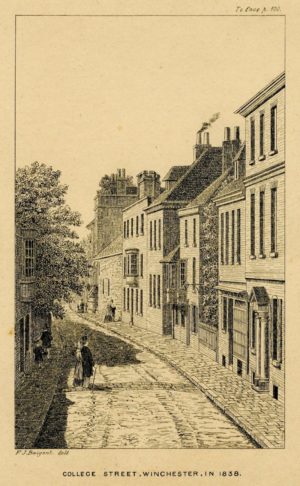

Jane Austen died at number 8 College Street, Winchester. We know this because there’s an elegant plaque on the wall to tell us. We also know that she wrote to her nephew James-Edward in Oxford from ‘Mrs Davids, College St Winton’ in deliberately chirpy and self-deprecating language, mentioning ‘a neat little Drawg-room with a Bow-window overlooking Dr Gabell’s Garden.’ We also have the footnote in her nephew’s 1871 Memoir that ‘It was the corner house in College Street, at the entrance to Commoners.’

However, there are several problems in concluding from these facts that the house in question was number 8. First, the College Head Master’s outgarden was indeed the open space that lay along the north side of College Street from just opposite the bookshop to the College Bursary, number 7, but it was protected from the common gaze by an eight foot brick wall. The extent to which a view from the first floor window of number 8 overlooked a concealed garden on the opposite side of the road is open to question.

As for Mrs David, we know16Winchester College records (MDC/44/70), 1934 correspondence and Herbert Chitty’s notebook. that she was variously the landlady, between 1797 and 1843, of three houses in College Street, namely numbers 8, 9 and 10. She didn’t acquire the lease of number 8 until 1841, two years before she died, when she bequeathed the property to her nephew Frederick La Croix (a pastry-cook and confectioner). The leaseholder of number 8 in 1817 (when Jane died) was her first husband Gale Miller, also a confectioner, although he died in 1813, and so the entirety of number 8 may have been given over to lodgings; Jane and Cassandra occupied all the first floor. Number 9 College Street, the fine house set back somewhat and previously with a railed-off garden in front, was acquired by Gale Miller in 1806 and passed into the hands of his widow in 1813; she subsequently left the house to her niece Harriet Bracewell. Number 10 College Street was leased to Mrs David’s second husband, Matthew, in 1817 and at his death in 1835 Mrs David leased it to the College. We can see from this that Mrs David was pretty active in the College Street property market and it’s quite possible that she lived in number 9 and let numbers 8 and 10. Of these three houses, number 8 is the only one with a bow window.

As for the claim by Jane’s nephew James-Edward that she died in the house on the corner, he should certainly know what he was talking about, even writing over fifty years later, as he had been a Commoner at the College from 1814 – 1816 and was also one of the three men, with his uncles Edward and Frances, who attended the funeral. However, in 1817 the house on the west side of the corner passage to Commoners was a College tenement and which in 1822 became the home of Thomas Poole, the College’s head porter, with number 8 being next door. The substantial rebuilding of the old Commoners and construction of the new house for the Head Master didn’t take place until 1839 – 1842.

Until 1913/14 there were six properties on the north side of College Street, when numbers 4, 5 and 6 were pulled down; numbers 1 – 3 occupied the corner site and they were demolished in 1934. Numbers 4 and 5 had been the home of the College’s Quirister School until it was relocated to Kingsgate Street in 1882. These buildings were modest three-storey houses of no great distinction, similar to those on the south side of the street (number 4 had a bow window) and they were usually rented as shops and lodgings. College Street was thought to have a disproportionate number of confectioners and fruiterers (not surprisingly) and the shopping evidence is apparent in the many houses in the area still with mullioned bow windows at street level. There is no evidence to support the possibility that a first-floor window in the gable end of number 6 had a view, looking eastwards, over Dr Gabell’s garden.

The second problem concerning the attribution of number 8 involves the man who erected the first commemorative plaque on the house in 1891. This was Thomas F Kirby, Winchester College bursar from 1877 – 1907 and author of the Annals of Winchester College, published in 1892. He should have been a safe pair of hands in this matter but he was a dour and querulous solicitor who used his considerable powers of intransigence to frustrate the reforming campaign of the College’s great modernising Head Master George Ridding. In College correspondence dating from 1934, the Head Master A T P Williams in a letter to the Keeper of the Archives, the antiquarian Herbert Chitty, refers to a statement that ‘Kirby had put the tablet on the house where it is now without inquiry into the facts.’17Winchester College, op. cit.

Finally in all this uncertainty, there is the frequent oral testimony of Joseph Wells, grandfather of the P & G who gave their name to the College Street bookshop.18Winchester College, op. cit. Joseph Wells (1822 – 1890) ran the bookshop from 1845 and it was a matter of family lore through two generations that the Kirby tablet was an entire mistake, that the house Jane Austen died in was on the north side of the street and that it had an oriel window. A somewhat picturesque drawing of the street as it was in 1838 by Francis Joseph Baigent, antiquarian and son of the College drawing master Richard Baigent, shows such a property more or less opposite the bookshop.

Sources & links

As might be expected of one of the English-speaking world’s best-loved and most cherished novelists, there are many active websites for readers interested in Jane Austen. In no particular order the following sites offer interesting content.

- The Jane Austen Society of North America runs an excellent, informative and scholarly site.

- An excellent online resource for serious students of Jane Austen, Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts is the first substantial collection of creative writings in the author’s own hand to survive for a British novelist. The manuscripts of the six novels no longer exist but much of the rest of her output does and can be seen here.

- A wide-ranging account of the geography of Jane Austen’s life at A Jane Austen Gazetteer.

- Her life, times and works are discussed at a sister-site Austenonly.

- Molland’s is a merry and informative site for fans, named after a shop in Bath.

- The Republic of Pemberley, another lively site for addicts.

- The Jane Austen Society of the United Kingdom is a long-established membership organisation which honours the author and promotes interest in her life and work.

- Lithouses is a portfolio of homes and museums dedicated to two dozen British writers.

- Jane Austen’s House Museum celebrates the author’s home, curates its contents, and informs its visitors in a treasured setting.

- Chawton House Library, once home to her big brother and now home to the study and enjoyment of early English women’s writing.

Notes and references

| ↑1 | AUSTEN, Jane, 1933. Sense and Sensibility. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press |

| ↑2 | LE FAYE, Deirdre, ed., 2011. Jane Austen’s Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press |

| ↑3 | LE FAYE, op.cit. |

| ↑4 | FACER, Ruth 2010. Fiction in the Hampshire Chronicle 1772 – 1829. Available at www.chawtonhouse.org/library/chronicle.html |

| ↑5 | Venta Belgarum was the Roman name for Winchester. The poem is predicated on the legend of rain for the next forty days if it rains on St Swithun’s Day (15 July). Swithun was a Bishop of Winchester and and there is a memorial shrine in the cathedral. The once-fashionable Winchester race-track was on Worthy Down to the north of the city. |

| ↑6 | As Heathcote also had the living of Worting, between Manydown Park and Basingstoke, it’s quite possible that he lived there with his new wife in the handsome rectory, and let out the prebendal houses to which he was entitled. Or, he could just have attended to his parish once a week and chosen to live in the grander place nearer to his own family rather than his wife’s. |

| ↑7 | AWDRY, F, 1906. A Country Gentleman of the Nineteenth Century: Being a short memoir of the Rt. Hon. Sir William Heathcote, Bart., of Hursley 1801 – 1881. Winchester: Warren & Son. |

| ↑8 | CROOK, John, 1984. The Wainscot Book: The Houses of Winchester Cathedral Close and their Interior Decoration 1660-1800. Winchester: Hampshire County Council. |

| ↑9 | CROOK, op.cit. |

| ↑10 | Elizabeth Heathcote lived in the Close until 1826 when she and her sister Alethea moved to Southend House in Hursley to be near her grand-children and then, as she aged, into Hursley Park with her son and his immediate family. She died in 1855 and is interred in the family mausoleum in Hursley churchyard. Southend House was demolished in 1967. |

| ↑11 | LE FAYE, op. cit. |

| ↑12 | BECKETT, Matthew 2012. Lost Heritage. Available at www.lostheritage.org.uk |

| ↑13 | BERNARD, April, 2011. What I Hate About Writers’ Houses. The New York Review of Books, 22 December 2011, 78. |

| ↑14 | TRUBEK, Anne, 2011. A Skeptic’s Guide to Writers’ Houses. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. |

| ↑15 | WATSON, Nicola J, 2006. The Literary Tourist: Readers and Places in Romantic Victorian Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. |

| ↑16 | Winchester College records (MDC/44/70), 1934 correspondence and Herbert Chitty’s notebook. |

| ↑17, ↑18 | Winchester College, op. cit. |